It has been a weird couple of years. Masked and isolated, we’ve learned to rely on a gestural language of raised brows and smiling eyes. In Zoom meetings, we’ve become used to companionably lamenting the strangeness of video interaction. It is clearer than ever that communication is a layered and multi-faceted endeavour.

The long-running London International Mime Festival is a celebration of storytelling at its most experimental and determined, but this year there’s also a revelatory pleasure in the medium. There are no emails or lockdown soft-launch Twitter leaks here, no communication by miscommunication. Whether juggling the vagaries of political and personal identity, sketching aliens, baking bread or embodying gods, LIMF 2022 is an uplifting reminder that we can dare to say more than anxious commentary on the pandemic. Sometimes deliriously successful, sometimes falling just short, the performances this year nevertheless speak of a thrilling ambition to close the gap between display and comprehension, celebrating the power of live communication.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=38UxbUBPwhM

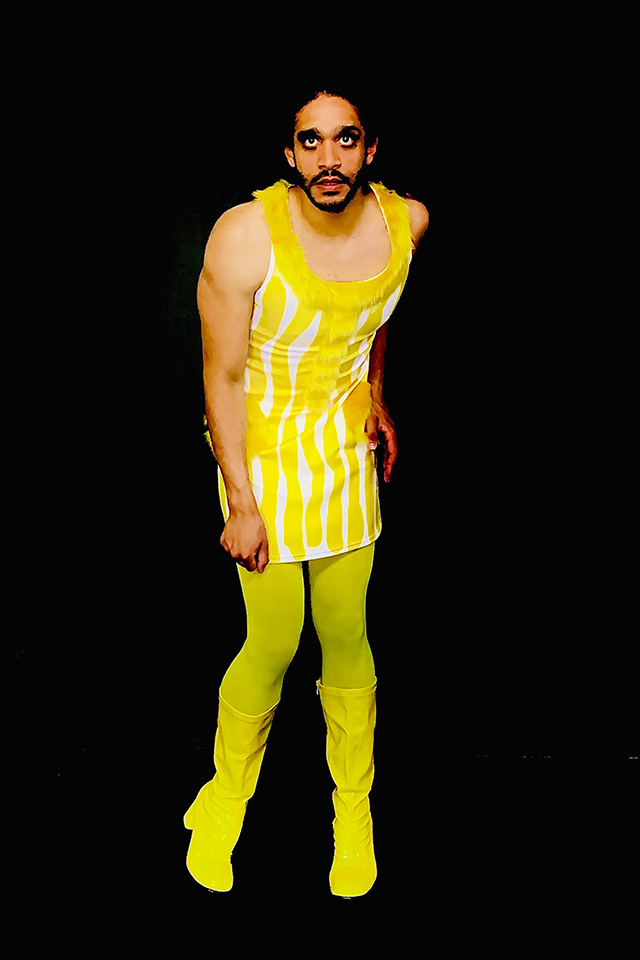

Jean-Daniel Broussé, (le) PAIN (FR)

Jean-Daniel Broussé, the son and grandson of a baker, is ending a family tradition. With the whimsical delivery of a stand-up comedian and the luscious, easy physicality of a street dancer, he grapples with the difficulty of stepping back from the legacy of the French family-run baker.

Watching (le) PAIN is like watching the performance equivalent of a patchwork quilt being sewn in real time. Disparate elements of memoir, demonstration and pure dance are stitched together to create the multi-hued whole. Broussé cheerfully demonstrates the work of breadmaking live on stage, with as much flourish and drama as he manipulates his body. He plays traditional French bagpipes, tells us a story in Occitan, offers us video interviews with his parents, and ends by feeding us freshly baked bread.

Broussé brings levity and wit to his physical storytelling. In one memorable segment, he folds himself into a full-body lycra sack and performs – with acrobatic sarcasm – the chemical process of bread rising. His mime of attempting to pass a stool is hilarious and stomach-piercingly evocative.

If this all sounds like a crazed cornucopia of disparate delicacies and skills, that’s exactly the audience experience. This short, small-scale piece couldn’t be longer or larger, or play to any but the most curious audience. But this might be (le) PAIN’s strength: in its very intimacy and specificity, it feels like a gift – to us, to Broussé family, to his own history.

Ka Bradley

Theatre Re: Bluebelle (UK)

Am I just too, you know, dancey? By rights, Theatre Re’s Bluebelle should have tickled my pleasure points. It’s a satisfyingly twisted, Brothers Grimmish tale of a barren queen and king who long for a child, and make a fateful pact with a fairy who grants their wish. (Newsflash: they don’t then live happily ever after.) It’s also big on atmosphere, with much moody sidelighting, and splendid folk-goth music played live on stage – a meandering montage of hurdy-gurdy rhythms, shiversome melodies and mysterious dissonances. The stagecraft is a delight: there are rope-pulley systems that hoik around props and scenery, cardboard crowns in the shape of antlers, an outsize coat that fits two villains at once, and much changing of costume and makeup so that the cast of six (including the two musicians) get to play a whole range of different characters. And the physical theatre – grotesque witchery, swirling magicians, questing gallops, lonely wanderings – is the stuff of good storytelling.

Perhaps that’s where my problem is: storytelling. There’s so much of it. It’s quite hard to follow, what with the tangled plot and multiple characters, each scene following fast on the heels of the last. There’s not much time for the pleasures or the depths of lingering longer – to feel the ambivalent beauties of Bluebelle’s solitude when she’s trapped in a translucent ball, the physical pain and personal elation of the queen as she gives birth, the enticingly orientalist undulations of the magicians as they cast their spell. I wonder if a choreographer rather than a theatre director might have been less tethered to plot, and given more leeway to savour and sensation. Or am I being too dancey?

Sanjoy Roy