While Russian ballet is always on tour worldwide, Russian contemporary dance remains so unseen one might even doubt its existence. Redressing this imbalance, Springback writer Anna Kozonina has just published a whole book on the subject, Strange Dances: Theories and Histories Around Experimental Dance in Russia, with the support of the Garage Museum of contemporary art in Moscow. Here, she summarises its first chapter, on experimental dance in Moscow and Saint Petersburg in the 2010s, as a way of opening a window onto this little known scene.

*

From Isadora Duncan to weird dances: a brief history of contemporary dance in Russia

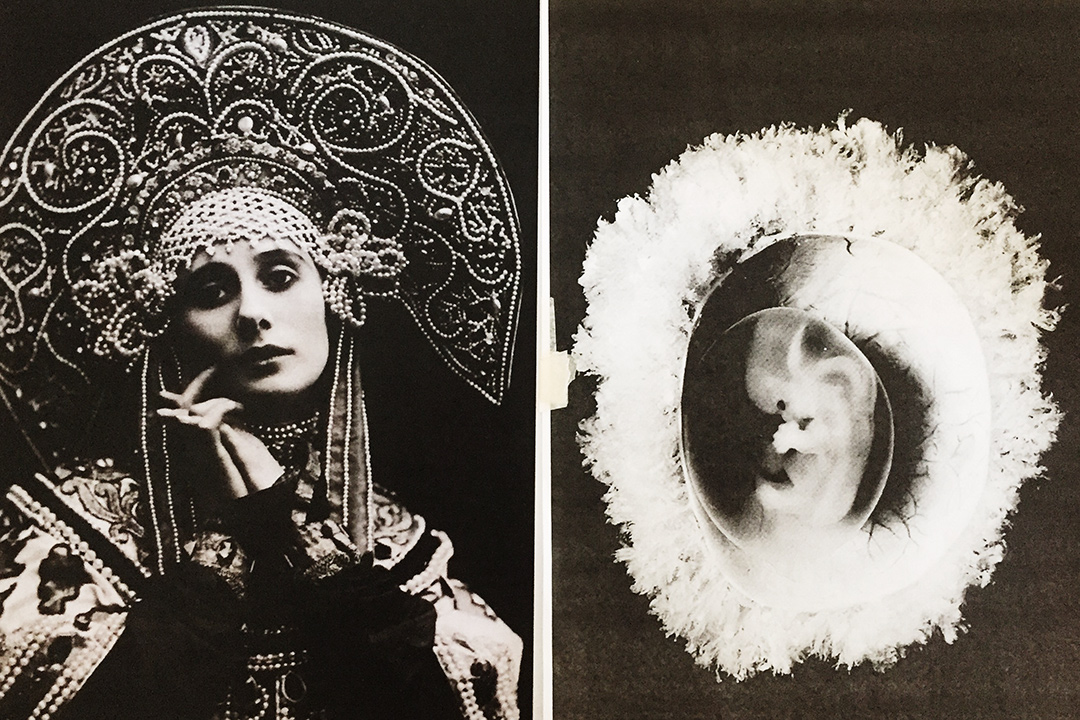

Modern dance appeared in Russia in the early twentieth century with the explosive popularity of Isadora Duncan’s school, and governmental support for movement studies. It is no secret that the great ‘free movement’ creator gained her main fame in Russia, and later in the Soviet Union. Duncan gave concerts in Saint Petersburg and Moscow in 1904–1905 and immediately won the hearts of the educated Russian public: the local audience absorbed the ideas behind free movement with great enthusiasm. Duncan’s dances, celebrating the ideals of antiquity, the harmony of the carnal and the spiritual, freedom of bodily expression, and a certain hedonism, inspired many local movement experiments. Her followers established their own schools and dance groups, developed plastic art studios and amateur dance activities. Dance clubs multiplied even during the first world war and after the revolution: almost every city had its own dance studio.1

The Soviet authorities quickly acknowledged the disciplinary and ideological potential of working with the body. At first, the enthusiasm of the ‘free movement girls’ was supported, for example, by Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Commissar responsible for the Ministry of Education: these dances were affordable and democratic, did not require large investments, and could become a tool for educating a new Soviet citizen.

But a few years after the opening of Duncan’s School in Moscow in 1921, party leaders already considered her style a bourgeois threat. Cultural policy redirected attention to physical education and disciplinary bodily training, and Duncan’s experiments were replaced by ‘dancing machines’, and ‘scientific organisation of labour’ (Soviet versions of Frederick Taylor’s ‘scientific management’). Individual bodily expression could not develop in the new reality of socialist machine-like culture. As theoretician Bojana Kunst said, if in the West ‘clumsy, still, expressive, lazy, dreamy, everyday and marginal movement is understood as an intervention of liberated singularity, in communist societies, such movement sabotages the whole social machine.’2 Conservative ballet became an official choreographic art – one reason for the tension that still exists between contemporary and classical dance in Russia. Until the 1960s ballet was not allowed to be modernised either: dance in performances had to be justified by the plot (the form was known as ‘choreodrama’). There would have been no chance for Georgiy Balanchivadze to become George Balanchine had he stayed at home: socialist art didn’t make friends with abstraction.

Contemporary dance re-emerged only in the late 1980s and early 1990s, along with the fall of the iron curtain and Perestroika, with the appearance of dance performers (and dance freaks!) who desired experimentation. Since then, several generations of choreographers have brought dance to the broader fields of contemporary theatre and art. The forerunners of the post-Soviet scene were diverse – including pantomime, amateur dance collectives, folk dance, and choreographic departments of cultural institutions – but rapid development started when Western dance techniques and aesthetics flooded into the country. Post-Soviet dance did not trust words, the very words of official culture and bureaucracy, which had been ‘performing’ Soviet everyday life for so long. The ‘truth’ was sought in the life of the body, so early Russian choreographers relied on bodily expression, reproducing the conceptual framework of modern dance.

The late 1990s and 2000s were the heyday of the Russian contemporary dance theatre. Kinetic Theatre directed by Sasha Pepelyaev, Olga Pona’s Chelyabinsk Contemporary Dance Theatre and Tatiana Baganova’s Provincial Dances were popular with the audience both at home and on tour. Dance theatres appeared all over the vast country: not only in Moscow and Saint Petersburg but also in Chelyabinsk, Perm, Yekaterinburg, Novosibirsk, Yaroslavl, Krasnoyarsk, Vladivostok, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, and other cities. For theoretician Natalia Kuryumova, this was for many reasons. In Russia ‘the concept of “theatre” was long comprehended as a space for free thinking and experimentation; choreographic “heresies” were free to roam there’. In addition, ‘the synthesis of widely differing art forms did not demand virtuosity and artistic perfection from dance’. Finally, ‘Russians favored allusions to theatrical plots, as orality remains the main axis of Russian culture.’3

Dance theatre leaders developed diverse aesthetics, but all were united by a wider common approach. The shows would often feature well-trained disciplined bodies dancing more or less articulated characters in staged settings, supported by background music or sound design. It was essential to show the individual at last separated from the collective body. It was important to impress the audience with technical skills and ‘original’ dance languages. Moscow-based dance agency TSEKH, which appeared in 1998, gave impetus to the development of new dance in Moscow: it produced shows, conducted international festivals, and organised showcases and tours, so that Russian dance could be shown abroad. The field gradually started to collapse when foreign funds began to leave the country in the late 2010s because of political reasons, and important venues and festivals closed.

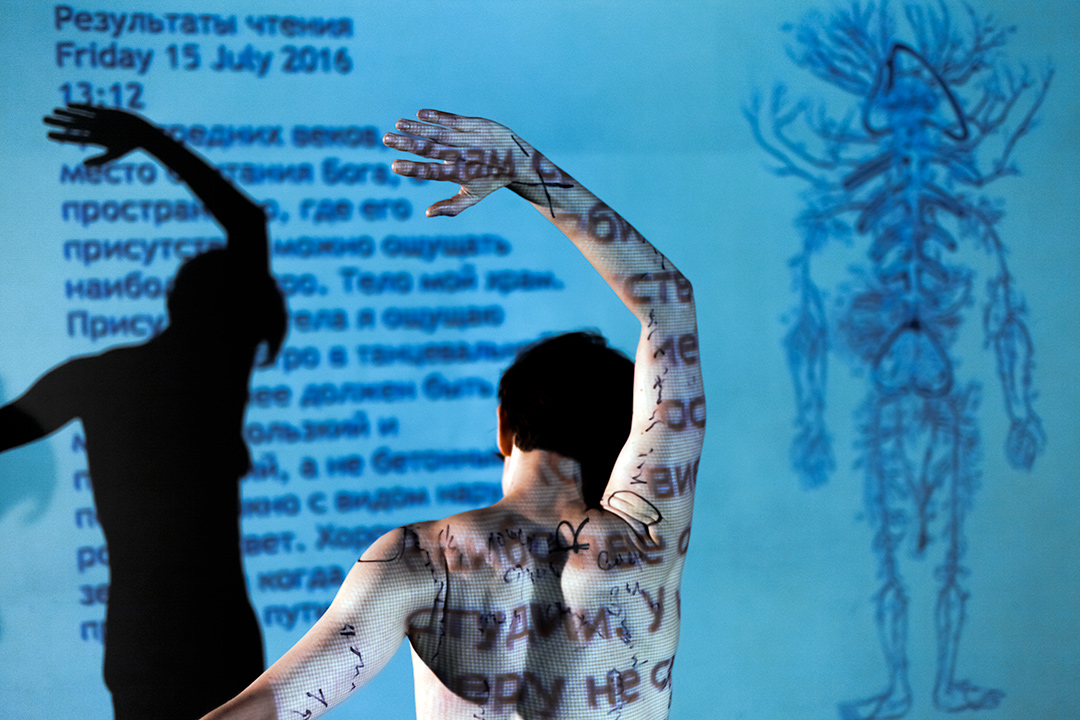

If the early 2000s were primarily associated with dance theatres built around choreographer-directors with a strong authorial style and a focus on creating a troupe, by the 2010s this smacked of conservatism. A new generation of choreographers, who today constitute the experimental dance scene of Moscow and Saint Petersburg, usually create pieces following a different logic. Their work is often based on a synthesis of seemingly contradictory approaches to dance and the body, the first connected with movement research and somatic practices, the second with theorisation, cultural and institutional critique. In other words, the body is not used as an instrument of expression, but perceived on the one hand as living matter, and on the other as a cultural artifact. Though the artists could rightly call this a crude generalisation, I propose it as a tool for understanding the new scene.

This scene is not big, but is essential in moving the Russian dance field forward. Among the most important dance artists are Alexandra Portyannikova and Daria Plokhova (‘Isadorino Gore’ dance cooperative), Tatiana Gordeeva, Nina Gasteva, Anya Kravchenko, Alexandra Konnikova and Alberts Alberts, Taras Burnashev, Anton Vdovichenko and Techno Laboratory group, Tatiana Tchizhikova and Anna Semenova-Ganz, Alexander Andriyashkin, Dina Khusein, Olga Tsvetkova, Asya Ashman, Katya Volkova, Natalia Zhukova, Darya Yuriychuk, Vik Laschonov, Vera Schyolkina, Alena Papina, Yulia Arsen, Marina Shamova; among grassroots initiatives, ‘Deystvie’ Laboratory and SDVIG community; and among curators, Katya Ganyushina, Anastasiya Proshutinskaya and Anastasiya Mityushina.

Somatics and criticism: a thriving union

When newly reborn Russia became part of the globalised world in the 1990s, there was little left for experimental choreographers other than to learn from foreign colleagues. Dancers strived for universality, technical skills and virtuosity, and presented their achievements to audiences. In the 2000s, other approaches started to proliferate in a scattered way, outside formal dance education. Little by little, the dance community started to immerse into somatics: Alexander technique, contact improvisation, Axis syllabus, peculiar forms of ideokinesis, Body-Mind Centering, release technique started to leak into festival and summer school programmes. For many, it was a revelation, as several post-Soviet dance pioneers confessed. Po.V.S.Tanze dance theatre’s co-founder Alexandra Konnikova (who had previously worked with Sasha Waltz, among others) said she was shocked when she discovered that the movement could arise from bodyweight release, not just muscle contraction. The former Kremlin Ballet soloist and Kinetic Theater dancer Tatiana Gordeeva, who contributed a lot to the spread of somatic knowledge in Russia, said: ‘It was scary to allow “regression”, to lie on the floor and listen to the body’. The departure from the balletic vertical, the dissemination of somatics, and practices of anti-spectacular dance suggested reassembling the very understanding of the body. It started to be seen as the material Other, as something possessing irrational wisdom, decision-making ability, and its own will. No longer concerned with showing it off, choreographers became interested in looking at its liquids, fascial tissue, skeleton and cells (things which in other arts often appear as ‘abject’, but in dance constitute very common somatic practices). Though not everyone was immersed in somatics per se, the dance of the 2000s and 2010s was interested in ‘regression’ and fallings. Their main apologist, perhaps, was Olga Tsvetkova, a native of Yekaterinburg and a graduate of Amsterdam’s School for New Dance Development, and now a curator at V-A-C contemporary art foundation, who even created the performance Falling Alphabet in 2014.

On the one hand, in new experimental dance, disciplined bodies and ostentatious virtuosity have been replaced by softer movement research. At the same time, the world of dance theatre illusion – with its theatricality, spectacle and synthesis of arts – gave way to ‘anti-representative’ aesthetics in which ‘the extraordinary’ was found in the ‘ordinary’. For Russian dance, historically associated with the figure of the monarch and with strongly hierarchical structures of power (ballet in tsarist Russia, disciplinary bodily control through physical education and sports in the USSR), the permeation of such trends also had a deeper political meaning: the discovery of bodily vulnerability, a rejection of displays of strength and superiority, the development of sensitivity and empathy, the study of biopolitical forces acting on the body. (Russians, always seeking utopian communities, have also managed to turn individualistic somatic practices into means for creating collective performances – a story I cover elsewhere in my book).

On the other hand, the new scene did not turn into a closed dance therapy circuit, since its representatives were able to develop another skill: critical analysis of the processes taking place both in society and in the field of art. So the study of the body ‘from the first-person viewpoint’ (as philosopher Thomas Hanna defined ‘soma’) was enriched by a conversation about the body as a cultural artifact involved in the work of theatre institutions, identity and gender politics, and biopolitics in general. Choreographers also started to question the boundaries of dance and spectatorship practices. In other words, Russian dance began to deal with the general problems of contemporary art and culture, adjusting them to its local situation and means of expression.